Democracy Is in Crisis. It Needs Human Development to Survive.

This past weekend, Romania gave the world a lesson in saving democracy from the imminent threat of fascism. Human maturity and wisdom played a crucial role, that other countries can learn from.

Before you jump into this article, a small announcement! We are in the final stages of admission for the upcoming cohorts (running on Americas/APAC and EMEA time zones) of our Foundation Diploma in Developmental Coaching, starting in July. This is the only ICF Level 1 coach certification course rooted in vertical development research. For more details and to book an interview, check out the program page.

For years, my birth country, Romania, has been among the top five countries of origin of new immigrants elsewhere, number 4 in the most recent OECD report, right after India, China, and Russia. This is despite Romania being part of the EU and NATO and having experienced huge economic growth over the past decade.

A staggering 5 million Romanians, out of 19 million total population, are now estimated to live abroad. The reasons for migration are highly complex and beyond the scope of this article, but suffice to say that many Romanians have left in the 35 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall (most of them once visas were lifted after Romania joined the EU in 2007) for two main reasons.

Many ran away from poverty and lack of economic opportunities, hoping to make a living in the West and support their families back home. The majority came from rural backgrounds and had been deprived of educational opportunities. They mainly settled in Central and Western Europe and took over low-paying jobs that the locals were not interested in doing anymore. Many refused to integrate into the societies where they lived and worked, considering their stay temporary (despite living there for years or even decades). They saw their lives abroad as a sacrifice - a means to the end of building a better future back home. They lived frugally, saved every penny and sent all their surplus back home - building houses in their villages of origin, most of which sat empty for years as their owners continued toiling abroad. Many left their children behind to be raised by relatives. They suffered the incredibly painful loss of being uprooted, while always pining for home and never truly putting down roots in their adoptive countries.

The second largest category of migrants was made up of educated professionals who lived in large cities, were experts in their fields, business owners or worked in comfortable corporate jobs and could afford to travel around the world. Many of them left too, not because they couldn’t live well in Romania, but because they sought a life away from the endemic corruption that persisted decades after our country broke free from its terrible totalitarian past. They increasingly felt that their values, which were mostly progressive, were not mirrored by Romanian society. They decried the underfunded education and health systems, the self-serving, incompetent politicians who seemed to always work against the taxpayer, and the busy, highly polluted cities. They left, spouses and children in tow, searching for a better quality of life for themselves and their families. They leveraged their knowledge and skills to build prosperous lives in their adoptive countries, seeking to integrate into their new homes and often giving up the desire to ever return to Romania, other than on holiday.

There are many nuances and countless stories between these two categories. Still, this overview will hopefully give you a backdrop for the near-death experience our democracy experienced only a week ago, when a far-right extremist, pro-fascist candidate faced off a pro-European, pro-democracy candidate in the second round of presidential elections.

The far-right candidate had entered the second round with a staggering score of 41% of the first-round vote, while the pro-democratic candidate was lagging far behind at a paltry 25% of the first-round vote. Whoever got over 50% in the second round would win, and the odds were stacked against the pro-European guy. Nobody in the history of free elections in our country had ever recovered such a gap. Still, he managed to perform an electoral miracle.

Through these elections, my birth country was split into two worlds, polarisation more painful and visible than ever. One pole zealously supported the far-right, ultranationalist candidate while the other desperately rallied behind the centrist, pro-European one. I found myself, even from my safe adoptive home in Australia, anxiously joining the latter pole, terrified at the prospect of Romania turning its face towards the East, away from Europe and falling back into authoritarian rule and economic hardship and the implication this would have on my family and friends. At the same time, I found myself fascinated by the devotion with which so many of my co-nationals embraced a narrative of hate and division and bought the blatant lie of a saviour leader come to deliver us all from the corruption of the ‘system’ - which, in the far-right narrative, included the European Union, intellectual elites and progressives of all kinds, who were suddenly seen as the enemy of an idealised conservative view where extreme traditional values, intolerance, authoritarianism and ultra-nationalism were seen as a holy grail.

I sought to understand the turbulent debates before these elections through the lens of vertical development, and I’ve put together a short guide to support people in reflecting on the value of mature leadership. I hope it helps inform the way we evaluate and choose our publicly elected leaders (and not only).

Do we need mature leaders?

In our field, we often call it vertical development, but in plain language, we might just call it wisdom or maturity (we could debate semantics here, but I choose to use these terms interchangeably). It’s a leader’s ability to know themselves well enough to manage their emotions, respond calmly to challenge and disruptive change, and to think systemically (aware of how things connect and how isolated problems are part of bigger patterns). Emotional and cognitive maturity allow leaders to understand complex issues, collaborate well with others for common outcomes, stay open to feedback, tolerate diverse viewpoints, and shift perspectives when presented with relevant new information.

Wisdom also means having an inner moral compass — doing what’s right not out of fear of punishment, but from a place of internalised integrity.

Maturity develops along a continuum — from very immature to highly mature — and not everyone grows at the same pace. Age, education, and life experience can help, but they don’t guarantee maturity. We can often sense someone’s maturity in the way they speak and behave, especially under stress.

Some key questions worth asking when we debate whether a politician or another is up for the task:

How do they handle themselves when provoked — do they stay calm or become aggressive?

How open are they to differing views — do they listen and inquire, or become defensive and dismissive?

Do they make decisions collaboratively, in the public interest, or discretionarily for personal gain?

Do they follow laws and rules because they understand their value, or break them when it’s more convenient?

Are their actions aligned with their stated values? For example, does someone who talks about peace react peacefully when provoked? Does someone who preaches integrity embody it?

We can assess maturity with specialised psychometric tools, but we can also get a sense of it by observing someone’s public discourse and analysing their track record.

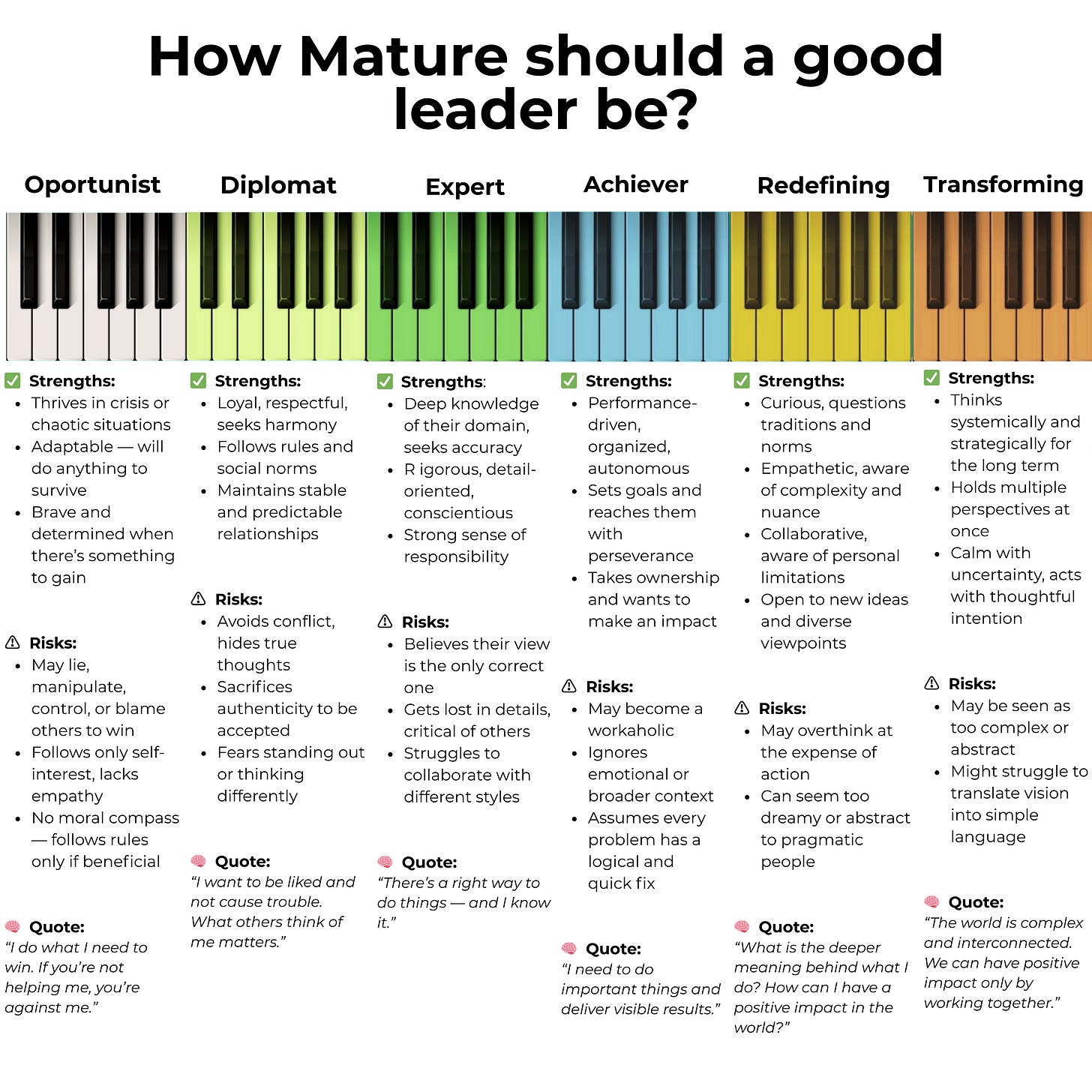

Below is an image summarising the key stages adults can grow through, each with its strengths and risks. Think of them like the octaves of a piano: the more maturity someone has, the more octaves they can access, and the more nuanced and complex the “melody” of their leadership becomes.

From Opportunist to Transforming

These stages range from Opportunist — an immature, egocentric mindset (most people outgrow it in adolescence, though sadly some remain stuck here and too many of those reach positions of power) — to Transforming, a highly mature stage from which leaders operate with self-awareness and systemic thinking (a stage reached by relatively few).

Every stage has its strengths and limitations, but if we want mature political leaders, we need to vote into office those who consistently demonstrate behaviours associated with the more advanced stages — the ones on the right side of the keyboard in that image.

As you reflect on what types of people you would like to lead the society you are part of, it’s worth turning your attention inward: Which stages show up in your own behaviour — in how you raise your kids, lead your teams, or interact at work?

Most of us move through several of these stages in daily life, and most of us are drawn to leaders who operate from similar stages.

Why does democracy need more mature political leaders?

Research consistently shows that more mature leaders lead more effectively, deliver better outcomes for the organisations/communities they serve, and have a more positive impact on the people who depend on them.

Mature leaders are more likely to keep their promises, show fairness and humility, are more realistic, better critical thinkers, more likely to be open to learning, and more willing to admit when they don’t know. They are less power-hungry and more tolerant of opposing views.

Organisational research confirms that mature leaders navigate turbulent times more effectively and are more inclined to act in the interest of the stakeholders they serve, not just their own self-interest. They are more equipped to create stability and trust, attract other competent and mature people around them, and collaborate to solve complex problems.

Leaders who operate from later stages are less tempted to abuse power (because they don’t need it as much to bolster their egos as their earlier stage counterparts do) and are more capable of acting with integrity, especially when hard decisions require personal sacrifice.

When it comes to leading a country, we have every reason in the world to want to choose the most mature leader possible. We would benefit from choosing not the candidate who shouts the loudest, but the one whose actions reflect more wisdom.

Let’s ask ourselves:

What’s each candidate’s track record?

How have they used power in the past?

How much maturity do they demonstrate in both big and small interactions?

Would you trust that person to run your child’s school or your community?

If not, why would you trust them to run your country?

These are important questions to reflect on when choosing someone who may shape the direction of a nation. In the case of Romania’s recent elections, the choices people faced would impact the country not just for the next few years, but possibly far beyond.

A choice between two very different kinds of leaders

In this election, Romanians were faced with two candidates at opposite ends of the psychological maturity spectrum.

On one hand, they saw a leader showing strong traits from the Opportunist stage — the most immature of all: egocentric, lacking integrity, driven by personal gain, but also charismatic, daring, direct, bold in breaking the norms and challenging the status quo in plain language. A leader with extreme authoritarian views, who voiced many certainties in a commanding (often aggressive) tone, whose actions consistently did not match his public declarations, yet a leader who has an extraordinary capacity to stir emotions and create viral content which spread like wildfire on social media. A leader with a talent for speaking the language of voters, pushing primal emotional buttons, like anger or fear, and stoking powerful bubbles of disinformation.

On the other hand, voters saw a candidate who had demonstrated traits from the Expert stage (a highly competent, award-winning mathematician, twice-elected mayor of the largest city in Romania, soft-spoken, precise, thoughtful, plain-looking, almost boring in his focus on facts versus rhetoric) and the Achiever stage (hardworking, goal-oriented, with a track-record of activism and reforms enacted from his public roles). Particularly during the electoral campaign, this unassuming candidate showed signs of Redefining maturity (showing up for all electoral debates his opponent avoided, taking hard questions from journalists even when they were deeply uncomfortable, reflective, measured in his reactions, cautious in avoiding big promises, open to collaboration), and even Transforming maturity (clear values, systems thinking, humility, recognition of the complexity of presidential role, speaking candidly even when the message did not win him political points).

This has been a choice between someone who “plays one octave” (very loudly) and someone who can play across many (in more muted tones). Voters had to choose between a compelling, righteous discourse rooted in blame, aggression, and revenge and a vision of stability, unity, and balance that favoured moderation over extremism. It seemed like an easy choice on the surface, yet it was not at all so.

The opportunist leader understood how to stir powerful feelings. His voters were mostly caught up in online resonance chambers where the same messages were repeated over and over again, the tone increasingly catastrophic, tapping into their deepest fears for the future and for the lives of their immediate families. This leader threatened terrible dangers lest he be elected, promised magical solutions to decades-old economic problems and made grandiose and blatantly unrealistic claims (such as giving everyone in the diaspora cheap houses so they could return and live at home again). He tapped into people’s insecurities and sense of inadequacy, talking about patriotism, the specialness of the Romanian people and promising retribution for all those who had been disenfranchised by a nameless, faceless ‘system’. He promised to burn it all down, so a glorious new Romania could be built anew, one where all those who had been left behind would be given priority, while the ‘corrupt elites’ would be shunned and punished.

The early-stage leader spoke to voters’ early-stage needs, presenting himself as a saviour, a “father figure” who would take care of everything if they just gave him all the power. Sound familiar?

Meanwhile, the more mature leader didn’t promise easy fixes. His discourse held fewer soundbites and made poor material for viral content. He focused on pragmatic solutions and often spoke in technical terms that were not easy to follow. He focused on policy, strategies and plans for economic recovery. He spoke about geopolitical tensions and their implications. He used nuanced terms and was hard to follow at times.

He treated his voters like equal dialogue partners, not children in need of protecting or saving. He didn’t claim to have all the answers, but invited co-creation and appealed to the collective wisdom and will for change. He didn’t promise certainty or instant change, but did embody respect for his voters and a commitment to working for the public good.

Luckily, enough Romanian voters had the patience to listen to what the mature leader had to say and did not get seduced by the noise of immaturity. But barely. The pro-European won with 53% of the vote while his extremist opponent got 46%. Of course, the far-right candidate did not admit defeat and continues to stoke division. Because, through the lens of early developmental stages, like Opportunist, the truth is optional and can change depending on where one’s interests lie. A competition is fair if you win, but it is rigged if you lose. It’s yet another recipe we have seen play out successfully in other parts of the world.

As a developmentalist and a child of communism, I have a deep respect for democracy, which, despite its profound flaws, I still consider our best path to building a world where humans can peacefully and sustainably co-exist while preserving the planet for future generations. I believe democracy is at risk as more and more early-stage leaders tap into our most basic instincts and fears, fuelled by a web of self-serving social media platforms that amplify noise and spread disinformation at scale.

I believe we need, more than ever, later-stage voters who can sift through information, look for substance underneath the bluster, distinguish truth from fiction, understand the bigger picture of a complex world and choose wisely so we can keep democracy alive. We need people who can critically examine their own thinking. People who can tolerate the pain of having their views challenged and become aware of the informational echo chambers we can so easily get caught up in on social media, and intentionally search for divergent points of view. We need people who can look past black-and-white narratives and examine the evidence before they make decisions. We also need people who are more self-aware, more in touch with their emotions and more resilient in the face of propaganda and systematic disinformation.

We also need to work together to address the systemic inequality that has been fuelling justified public anger. We need to lean in and truly listen to the pain of those who have a different political option. Those of us who like to think of ourselves as self-reflective should start by looking in the mirror and asking ourselves how we might be contributing to this toxic polarisation that is tearing our societies apart.

I honestly think democracy will not survive in the absence of more human maturity and wisdom on all sides, particularly not in an age when most people get their information off the internet and AI is rapidly changing everything we know about how we communicate, connect, debate, learn, work and live our lives. Our education systems are not equipped for growing wise, mature humans who know how to listen, ask questions and dialogue with each other, and that might be the place to start. But that is a story for another time.

For now, democracy still lives in the small corner of the world where I come from, while being under assault in other parts of the world. This is not a battle between good and evil - it’s one big storm we are all caught up in, and which we can only navigate safely if we start leaning into the discomfort beyond our own bubble rather than the pleasure of the ever-present confirmation bias inside of it.

Dive deeper

I hope you’ve enjoyed this article. If you are curious to dive more deeply into learning about Vertical Development and how it might impact your work and life, check out our online library of webinars and certification programs accredited by the International Coaching Federation. If you choose to become a paid subscriber to this substack, you will receive complimentary access to all our webinars and a 50% discount on our long-form online programs, including our “Vertical Development Practices for Coaches”.

If you are seeking to train as a developmental coach and get your first ICF credential, admissions are now open for the next cohorts for our ICF Level 1 Foundation Diploma in Developmental Coaching starting in July 2025 (now running on both Americas/Apac and EMEA time zones). The early bird offer ends on the 30th of May. Check out the Program Page for details and reach out for an interview.

Spread the word…

If you want to bring your bit to building a wiser, more conscious world, I hope you share this article with others who could benefit from the learning.

and, if you haven’t done it yet, Subscribe!

Join your nerdy community and let’s keep on staying curious and learning from each other.

Dear Alia

I appreciate many points in your article and wholeheartedly agree with the calling for the wise, mature leader.

However, I consistently feel sad and pained by the unbalanced notion of the "lower" developmental stages, the "bass section" in your piano metaphor. For a piano to play a full, rich, complex music, each key needs to be revered, loved and practiced. In this current narrative, when the "bass section" is seen as immature, and "treble section" is seen as mature, how can the pianist practice the keys in the bass section?

For me, the earlier development stage represents an original, embodied sense of wholeness gifted to each human at birth, before our cognitive development. In the Taoist tradition, we call it the "prenatal source of wholeness" 先天元气. One core principle of the practice of the Tao is to surrender the self cultivated from our cognitive development to serve the prenatal, the original wholeness.

The idea and practices of prenatal wholeness can been seen in many indigenous and Earth-based cultures. In China, its related cultural practices and systems have been destroyed through colonization and capitalism. To me, the narratives of the "opportunists" is a pathological version of the earlier stages, when the "prenatal wholeness" is unseen, unappreciated, and unpracticed.

A wise, mature leader needs be able to play every single key on the piano with clarity and presence. How could someone play the bass section with a full heart devotion, with this pathological view of those keys?

In June, I am going to present my work of the adult development from an east-west perspective in a professional gathering in Seattle. I hope one day we can talk about this in person.

With respect and appreciation of your work

Spring