Two Worldviews at Davos: What the Carney-Trump Contrast Reveals About Leadership in Our Time

Two world leaders addressed the same global audience at the same moment in history and gave us a rare window into fundamentally different ways of making meaning. What can we learn from it all?

I watched Mark Carney’s and Donald Trump's speeches at Davos with that particular mix of fascination and dread that seems to accompany so much of our collective news-watching these days. I also watched them with a profound sense of grief. As a Romanian-Australian, I carry the transgenerational trauma of being born and spending my early years in a dictatorship, alongside the privilege of living my youth and adult life freely, first in a young democracy, then in an established one.

I have seen and felt what the ‘might makes right’ worldview does to people who live in its realities every day. I have also tasted the liberty of living in a society where my rights as a citizen felt like an unshakable certainty. And I have known the anxiety and uncertainty of living somewhere in-between these extremes.

And as someone who has spent years studying how adults develop through stages of increasing maturity, I found myself unable to watch these speeches without my researcher’s lens clicking into place. Because what unfolded on that stage was more than political statements. It was a demonstration of two fundamentally different worldviews in action, both with vast (and differing) implications for all of us, whether we live in more or less democratic societies, near or far from the seats of geopolitical power.

I want to be clear from the start that I’m approaching this analysis with my own perspective and values. If your political leanings differ from mine, that’s perfectly fine, because this article is less about which worldview is “right” and more about what an adult development lens can help us learn from each of them. I think those lessons truly matter for all of us, as we think about what kind of future we would like to live in and what kind of leaders we need to build it.

For those new to the concept of vertical development, this is a branch of developmental psychology that studies how adults continue to evolve through stages of cognitive, emotional and interpersonal maturity throughout their lives. These stages shape how we understand power, what motivates us, how we relate to others and how we navigate complexity. The model I use most often in my work draws on the work of Bill Torbert, David Rooke, and Susanne Cook-Greuter, and distinguishes between seven stages of development: Opportunist, Diplomat, Expert, Achiever, Redefining, Transforming, and Alchemical.

I often compare these stages to the octaves on a piano. When we talk about someone’s “developmental repertoire”, we mean their capacity to make sense of the world in increasingly sophisticated ways. The research is compelling: the more ‘octaves’ a leader can ‘play’, the more effective they tend to be at dealing with complexity. And few leadership roles are as complex as that of a head of state.

Power

One of the clearest windows into developmental maturity is how a leader understands and exercises power. At earlier stages, power tends to be conceived as “power over” others, as something you wield to get what you want. At later stages, power becomes more relational, understood as “power with” and even “power to” others.

Trump’s speech offers a remarkably consistent portrait of power as leverage. Throughout the address, success is framed as the result of credible threats and the willingness to follow through.

Consider his account of negotiating prescription drug prices with France: “I said, ‘Here’s the story, Emmanuel, the answer is, you’re going to do it. You’re going to do it fast. If you don’t, I’m putting a 25% tariff on everything that you sell into the United States, and a 100% tariff on your wines and champagnes.’ (…) ‘No, no, Donald, I will do it. I will do it.’ It took me, on average, three minutes a country.”

Or take his recounting of negotiations with Switzerland. After the Swiss President expressed resistance, Trump notes: “She just rubbed me the wrong way, I’ll be honest with you (…) And I made it 39%, and then all hell really broke out.” Power here operates through dominance, and relationships are scored by who yields to whom.

This is very much the logic of what developmental researchers call the Opportunist stage, a worldview which Susanne Cook-Greuter describes as “aware of his or her physical strength and size (or status power) and may use it to intimidate others in order to get what they want. Opportunists are generally wary of others’ intentions and tend to anticipate the worst. Everything to them is a war of wills. Life is a zero-sum game. It is important to realize that much aggression may stem from profound uncertainty, a sense of vulnerability and being confronted by a world whose rules they may not actually understand. In a self-protective move, Opportunists may be aggressive to pre-empt expected strikes of others. They are people of action, not of thought and planning.”

Trump’s aide, Stephen Miller, echoed the same Opportunist worldview in a CNN interview that got widely reported and analysed: “We live in a world, in the real world, Jake, that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power,” (…) “These are the iron laws of the world since the beginning of time.”

Do the immutable realities of the world determine how we should think? Or is it our pre-existing assumptions that make us see exactly what we expect?

Carney’s speech reveals an entirely different worldview and relationship to power.

He explicitly names the impact of the Opportunist mindset on those at the receiving end of it: “When [middle powers] only negotiate bilaterally with a hegemon, we negotiate from weakness. We accept what’s offered. We compete with each other to be the most accommodating. This is not sovereignty. It’s the performance of sovereignty while accepting subordination.” He also warns about the perils of being the weaker side in a duo where the other operates from Opportunist: “If we’re not at the table, we’re on the menu.”

But he doesn’t stop here. He specifically acknowledges the limitations and the perils of ‘power over’ and offers a vision of ‘power with’ as an alternative, more sustainable worldview: “Collective investments in resilience are cheaper than everyone building their own fortresses. Shared standards reduce fragmentation. Complementarities are positive sum.”

The late Professor Bill Torbert called this vision of power “mutual praxis,” understood as shared, reflexive action and inquiry through which people simultaneously transform themselves, their organisations, and their broader political/scientific systems. In this worldview, power is not something anyone has or can be extracted through dominance, but something that grows through relationship and mutual exchange. But that requires a capacity to see life as much more than a zero-sum game. And, judging by these two speeches, only one of these two leaders holds that view.

Perspective-taking

Another revealing developmental marker is how leaders understand and integrate different viewpoints. At earlier stages, there is typically only one perspective (one’s own), and those who see things differently are deemed wrong and automatically become enemies. At later stages, leaders develop the capacity to genuinely comprehend how others see the world, even when those perspectives conflict with their own.

Trump’s speech demonstrates a consistent single-perspective orientation. The world exists in relation to American interests, and other nations matter only as far as they serve or obstruct those interests: “When America booms, the entire world booms. It’s been the history. When it goes bad, (…) you all follow us down, and you follow us up.”

Alternative viewpoints tend to be dismissed rather than engaged with. Windmills are for “stupid people.” European countries are “not even recognizable anymore, frankly… they’re not recognizable.” The press is “terrible… crooked… biased.” Within this frame, disagreement signals either ignorance or bad faith.

Carney’s speech, by contrast, demonstrates what we might call perspective fluidity. He quotes Václav Havel at length, drawing on a Czech dissident’s analysis of communist systems to illuminate the present moment. The story of the shopkeeper’s sign shook me to the core:

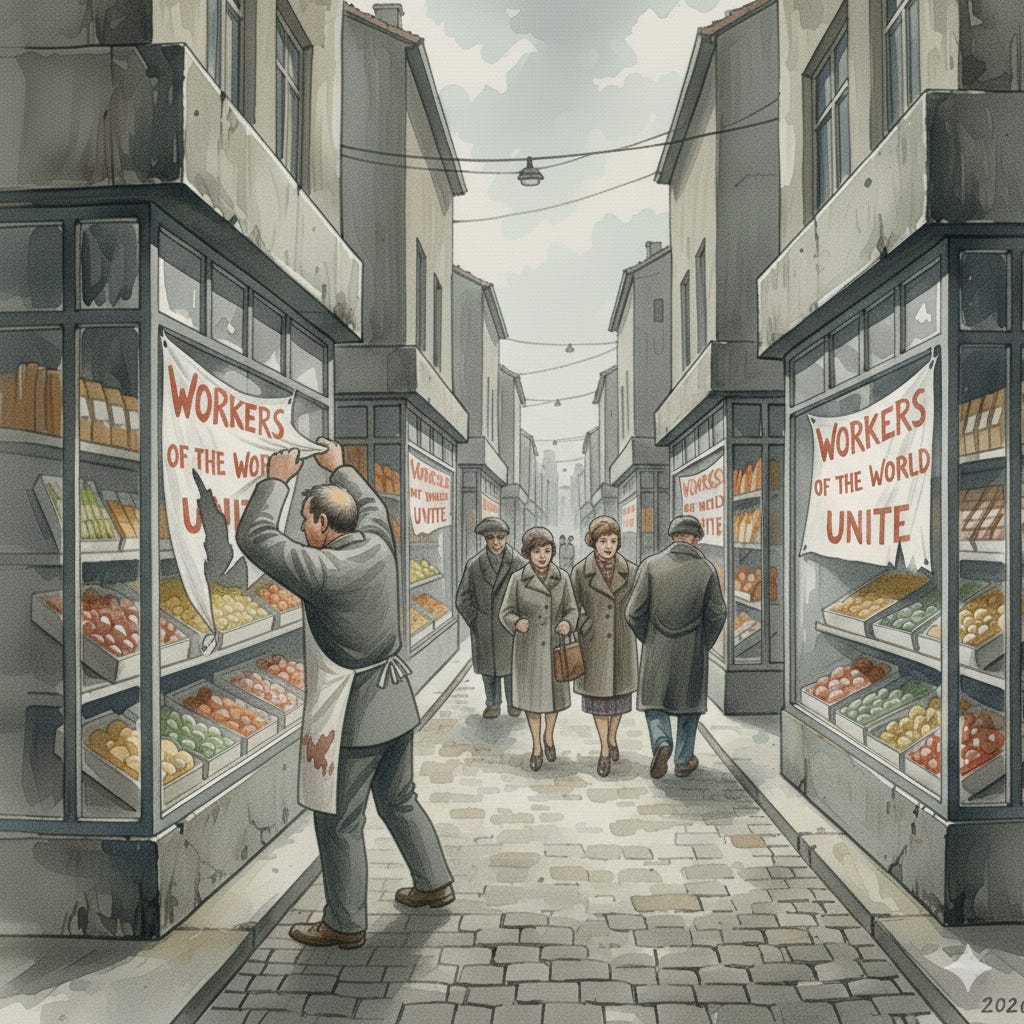

In 1978, the Czech dissident Václav Havel, later president, wrote an essay called The Power of the Powerless, and in it, he asked a simple question: how did the communist system sustain itself?

And his answer began with a greengrocer.

Every morning, this shopkeeper places a sign in his window: ‘Workers of the world unite’. He doesn’t believe it, no-one does, but he places a sign anyway to avoid trouble, to signal compliance, to get along. And because every shopkeeper on every street does the same, the system persist – not through violence alone, but through the participation of ordinary people in rituals they privately know to be false.

Havel called this “living within a lie”.

The system’s power comes not from its truth, but from everyone’s willingness to perform as if it were true, and its fragility comes from the same source. When even one person stops performing, when the greengrocer removes his sign, the illusion begins to crack

This story painfully reminded me of the Communist Party membership card my own parents had disgustedly discarded at the bottom of a random drawer nobody ever opened (except a curious kid), a sad reminder of their lack of freedom and forced obedience for the sake of survival.

Carney references Finnish President Alexander Stubb’s concept of “value-based realism.” And he explicitly names Canada’s own complicity in comfortable fictions: “We knew the story of the international rules-based order was partially false… And we placed the sign in the window. We participated in the rituals.”

Perhaps most tellingly, he articulates the logic of his adversaries without demonising them: “Great powers can afford for now to go it alone. They have the market size, the military capacity and the leverage to dictate terms.” This is the capacity to hold your own position while genuinely comprehending how others arrive at different conclusions.

At late stages, leaders are able not just to notice but to fully inhabit and actively work with paradox. There is a beautiful example of this ability in Carney’s speech, as he talks about the approach to solving global problems called “variable geometry”. He describes this as “different coalitions for different issues based on common values and interests. So, on Ukraine, we’re a core member of the Coalition of the Willing and one of the largest per capita contributors to its defence and security. On Arctic sovereignty, we stand firmly with Greenland and Denmark, and fully support their unique right to determine Greenland’s future. Our commitment to NATO’s Article 5 is unwavering, so we’re working with our NATO allies (…) On plurilateral trade, we're championing efforts to build a bridge between the Trans Pacific Partnership and the European Union, which would create a new trading bloc of 1.5 billion people (…) This is not naive multilateralism, nor is it relying on their institutions. It’s building coalitions that work – issue by issue, with partners who share enough common ground to act together.”

The paradox here is that while the sets of values shared within each coalition differ, these coalitions can coexist, and one country, such as Canada, can initiate and be part of a whole constellation of such coalitions without betraying its fundamental moral principles. It is this acceptance of paradox that allowed Carney to sign a trade agreement with China just the other week, upholding a mutual commitment to economic benefit (and shifting away from the US as an act of self-preservation), while also being part of the Coalition of the Willing for Ukraine, speaking up for Greenland and standing firm with NATO.

By contrast, the one-perspective response is: “Canada gets a lot of freebies from us, by the way. They should be grateful also, but they’re not. I watched your Prime Minister yesterday, he wasn’t so grateful. They should be grateful to US, Canada. Canada lives because of the United States. Remember that, Mark, the next time you make your statements.”

Attention

Development is also reflected in where leaders direct their attention. Bill Torbert described four territories of experience that we might place our attention on at any given time. Maturity comes with the ability to notice more than one territory, and, at the very late stage, the ability to observe all four at the same time.

The first territory is the outer world - I notice what happens outside of me. The second is my thoughts, emotions and behaviours - I have opinions, and I react to what happens outside. The third territory is the space of values and assumptions - I am conscious of my own assumptions, values and principles which inform my actions. And finally, the fourth territory is that of intention - I engage with reality in a purposeful way, I choose my actions to follow a conscious intention. It is a powerful act of self-awareness to notice what is happening in all four territories and an act of courage to align your actions to those observations.

Trump’s attention seems to reside solely in the first two territories. Something happens, he has an emotion and a reaction. Within the speech, he shifts between the economy, windmills, Greenland, Venezuela, nuclear weapons, the Swiss President’s demeanour, prescription drugs, cryptocurrency, housing, pirates, and Somalia. There is no connecting narrative, nor any reflection on assumptions. There is only one intention, assumed, never questioned: establish and maintain dominance in every relationship.

Carney’s attention operates differently. From the outset, he steps into the third territory, naming the shifting landscape of global assumptions on power - “It seems that every day we’re reminded that we live in an era of great power rivalry, that the rules-based order is fading, that the strong can do what they can, and the weak must suffer what they must. And this aphorism of Thucydides is presented as inevitable, as the natural logic of international relations reasserting itself.”

Then he proceeds to shift attention into the second territory, showing what the impact of taking such assumptions for granted has on the behaviour of geopolitical actors: “And faced with this logic, there is a strong tendency for countries to go along to get along, to accommodate, to avoid trouble, to hope that compliance will buy safety.” He then moves back to the first territory, reminding everyone that their current behaviours are not working, as evidence well shows: “Well, it won’t. So, what are our options?”

Carney’s discourse is an elegant dance through the four territories, in which he challenges the world to question its own assumptions, to acknowledge that it has, in many ways, been part of upholding “a pleasant fiction” that was not called such because it served the actors who participated in it: “We knew the story of the international rules-based order was partially false that the strongest would exempt themselves when convenient, that trade rules were enforced asymmetrically”. He challenges the world to face the realities of the moment and ask itself what is it that it truly wants - what’s its intention (territory 4)?

“We are taking the sign out of the window. We know the old order is not coming back. We shouldn’t mourn it. Nostalgia is not a strategy, but we believe that from the fracture, we can build something bigger, better, stronger, more just. This is the task of the middle powers, the countries that have the most to lose from a world of fortresses and most to gain from genuine cooperation.

The powerful have their power.

But we have something too – the capacity to stop pretending, to name reality, to build our strength at home and to act together.“

Time

Our relationship to time is closely connected to attention in the developmental continuum. At the earlier stages people think in short time horizons. Time is linear. Action is immediate. At the later stages broader time horizons unfold. Time becomes a web, the actions of today reverberating over generations.

Trump’s time horizon is narrow:

“Yesterday marked the one-year anniversary of my inauguration”

“Since the election, the stock market has set 52 all-time high records”

“Over the past three months, core inflation has been just 1.6%”

“In 12 months, we have removed over 270,000 bureaucrats from the federal payrolls”

Success is measured in 12-month cycles, quarterly projections, and stock market records. It’s also measured in how fast things happen:

“It took me, on average, three minutes a country”

“I said, ‘No, not only am I not kidding, you’re going to have your approvals within two weeks.’”

“Within two months, it was great. Within three months, it’s like, it’s really a great place”

“My biggest surprise is I thought it would take more than a year, maybe like a year and one month, but it’s happened very quickly.”

Meanwhile, Carney opens by going back two and a half thousand years to remind us that Thucydides' wisdom is still perfectly adequate for describing our modern-day conundrums, and perhaps to remind us that our woes are as old as mankind. He then reflects on the crumbling of decades-old paradigm: “For decades, countries like Canada prospered under what we called the rules-based international order.”

When he brings his attention to the now, he does it to highlight a transformation, a shift from something into something else: "We are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition." He looks at the recent past to highlight actions taken with a view to the future: “We’re doubling our defence spending by the end of this decade”; “The past few days, we’ve concluded new strategic partnerships with China and Qatar.”

He thinks in systemic consequences over time, and the impact that the choices middle powers make now will have on the global order of tomorrow. This is consistent with what Bill Torbert used to call “timely action”, which, for him, meant taking choiceful action with others, at the right time, for a higher purpose. In this sense, the whole of Carney’s discourse is a call for timely action.

Collaboration

Trump’s collaborative framework is explicitly transactional. Life is a zero-sum game, and there is no such thing as a win-win situation. Relationships are scored: “We’ve never asked for anything, and we never got anything.” Value flows in measurable units: “We give so much, and we get so little in return.”

The NATO relationship is framed entirely in these terms: “We want a piece of ice for world protection. And they won’t give it… So they have a choice. You can say ‘yes’, and we will be very appreciative, or you can say ‘no’, and we will remember.”

Carney’s collaborative vision has a different structure. He describes “variable geometry, in other words, different coalitions for different issues based on common values and interests.” Canada is pursuing partnerships that create “a dense web of connections across trade, investment, culture.”

This approach recognises that collaboration is contextual. Different configurations serve different purposes, and the network itself becomes a source of adaptive capacity. Within this frame, relationships are investments for collective outcomes, rooted in trust and shared values rather than mere transactions, and their value often becomes apparent only over time.

The Opportunist’s Superpower

I want to pause here and acknowledge something important, because it would be too easy to turn this analysis into a simple hierarchy where later equals better.

The Opportunist has a superpower that many people at later stages lose. People at this stage are often unafraid to shake up the status quo. Because they have limited self-awareness, they also tend to have limited self-censorship. Cultural taboos don’t constrain them the way they constrain others. This gives people at the Opportunist stage remarkable courage to say the unspeakable (and do the undoable).

Trump’s capacity to channel collective anger, to voice grievances that others would moderate or suppress, has been, in many ways, central to his appeal. His willingness to say exactly what he wants, when he wants it, resonates with people who feel unheard or unseen by traditional politicians. In many ways, he has channelled the righteous and justified anger of those who were not served by the “fantasy” aspect of the rule-based order, nor by globalisation, nor by the unconstrained energies of capitalism. The Opportunist wavelength can reach places and channel energies that later-stage communication simply cannot.

Late-stage mindsets learn to harness the energies of the Opportunist in more sophisticated ways. In Carney’s discourse, there is an impetus for action, a sense of urgency, a reminder that the time to wake up has come, that consequential choices are ahead of us and that we cannot afford to procrastinate.

While people like Carney channel the Opportunist by urging others to “take the sign out of the window”, the full-blown Opportunist is likely to throw a rock at said window. But what good is a street full of devastated shops? What good is a world whose anger at inequality has turned into a tornado of self-destruction?

What This Moment Asks of Leadership

Perhaps the key question here is “leadership in service of what”?

As a researcher and facilitator of leadership education, my own motivation has always been rooted in a deep desire to help foster wiser leadership for a world where more people can co-exist in peace, with freedom, dignity, with a roof over their heads, food on their tables and access to education and health; on a planet we are protecting and whose resources we’re using sustainably; for a future where our children can thrive, travel, explore and live life fully without that taking away anything from others. That aspiration is surely utopic, but that hasn’t prevented me from holding, for I have learnt since my earliest days that living in fear, darkness, cold, having your choices stripped away from you, having your environment stunted and destroyed is no good way to live.

Carney’s speech explicitly names a rupture in the world order. He argues that the fictions that sustained global cooperation are collapsing, that economic integration is being weaponised, and that “if great powers abandon even the pretense of rules and values for the unhindered pursuit of their power and interests, the gains from transactionalism will become harder to replicate.”

If he’s right (and I think the evidence supports his analysis), then the developmental demands on our leaders are intensifying and facing us with some choices to make.

If we accept that our future is a world of zero-sum competition, it requires only the ability to win bilateral negotiations. The Opportunist will be the engine of that world, and the price will be unthinkable for everyone on the losing end of every zero-sum round of any game.

If we still hope for a world where the common good has a chance, that world will need to coordinate on climate, AI governance, migration, future pandemic response, and work mightily hard for geopolitical stability - and that requires something more than Opportunist.

It requires leaders who genuinely operate from later stages of development. Leaders who can hold multiple perspectives simultaneously, who can build coalitions around shared values rather than shared enemies, who can think in systems rather than transactions, who can resist the pull of short-term wins for the benefits of long-term flourishing, who are humble enough to not try do it alone and who cultivate patience, inquiry and sound judgement in the face of overwhelming complexity.

For those of us working in leadership development, these two speeches encapsulate a choice and perhaps represent a sobering invitation. How much of what passes for leadership development in organisations today actually cultivates the kind of sophisticated capacities we need to steer our way out of this messy place? How much of our education fosters inner growth in the young people who will become the leaders of tomorrow?

Too much of our field (of leadership development) remains focused on performance goals and horizontal development (more skills, more frameworks, more techniques). What I believe this moment seems to remind us of is that we need a deeper understanding of vertical development with all its streams - cognitive, emotional, moral, interpersonal. If we’re hoping to lend a hand to building the world Carney is describing, we need to learn to expand our underlying capacity to hold complexity, tolerate ambiguity, and build relationships across difference.

Watching Trump and Carney at Davos, we weren’t just seeing two politicians with different views. We were seeing two different worlds. I, for one, was paradoxically reminded both of how small and powerless I am in the grand scheme of things, and, at the same time, of how consequential my small actions can be in building, in my own small sphere of influence, a microcosm of one of these two worlds.

Even writing this article on a Substack where I generally strive to avoid political controversy is a small way of ‘taking the sign out of the window’. I wonder what’s yours?

Dive deeper

I hope you’ve enjoyed this article. If you are curious to dive more deeply into learning about Vertical Development and how it might impact your work and life, check out our online library of webinars and certification programs accredited by the International Coaching Federation. If you choose to become a paid subscriber to this Substack, you will receive complimentary access to all our webinars and a 50% discount on our long-form online programs, including our “Vertical Development Practices for Coaches”.

If you are seeking to train as a developmental coach and get your first ICF credential, check out our ICF Level 1 Foundation Diploma in Developmental Coaching - next cohort starts in July 2026 (now running on Americas/Apac time zones). Check out the Program Page for details and reach out for an interview.

Spread the word…

If you want to do your bit to build a wiser, more conscious world, I hope you share this article with others who could benefit from the learning.

And, if you haven’t done it yet, subscribe!

Join your nerdy community, and let’s keep on staying curious and learning from each other.

What a brilliantly balanced piece on leadership development! The section acknowledging the Opportunist's superpower really stood out - it takes serious self-awareness to resist making this a simple hierachy where 'later equals better'. That nuance is exactly what's missing in most political discourse. I've definately noticed how people with less self-censorship often voice things that need saying, even if clumsily. The real challenge is channeling that raw energy constructively, dunno if that's even truly possible.

Thank you Alis. I could listen to your insights all day. I have great appreciation for the way you write too, so pragmatic.