What Is Vertical Development, Really?

A new White Paper and a map for the messy terrain. This nerdy dispatch is particularly dedicated to those of you who are actively involved in building and faciliating leadership programs.

If you’ve spent any time in leadership development circles lately, you might have noticed that “vertical development” is having a moment. Consulting firms, executive coaches, corporate learning functions: everyone seems to be talking about it.

I do think this is largely a good thing (while openly admitting my own status as a biased participant in the field). I believe the shift from “more skills” to “expanded capacity” represents genuine progress in how we think about growing leaders. Also, if we merely look at the state of global leadership right now, it might be fair to say we can and really need to do better, so the case for vertical development’s utility seems pretty solid.

But as a ‘paracademic’ who has spent years immersed in this field, I’ve noticed that, despite its popularity, there is significant confusion about what vertical development actually is, how it is measured and, most importantly, how it can actually be fostered through deliberately designed learning experiences.

Different assessment tools get conflated as though they measure the same thing. Practitioners swear by one theory or another or equate ‘developmental work’ with a particular school of thought - usually the one they themselves got trained in. Organisational clients themselves often request programs to “move our leaders into ‘higher’ developmental stages” without clarity about what types of stages we are talking about, which dimension of development we’re targeting or even whether ‘higher’ is necessarily better or fit for purpose.

I watch thoughtful L&D leaders struggle to make sense of competing models and methodologies, and for good reason. The research landscape in our field is quite fragmented, and to date, there have been few attempts to cross-pollinate across the various traditions. There are many reasons for that fragmentation, some of which might have to do with the natural attachments of researchers to their own theories, which they have spent decades honing, and others might have to do with the challenge practitioners have of staying abreast a vast patchwork of scientific perspectives while also doing the program design, facilitation, intensive day-to-day client work that is their bread and buttter.

While it is easier to just pick one theory and stick with it, I would argue that in the current global context, where the polycrisis meets the metacrisis and humanity seems to be in SO much trouble, we need to step beyond our ideological differences into a bigger understanding of the adult (vertical) development field and more effective interventions that shift the needle on good leadership in this hectic age.

Both research and practice point to the fact that there is no single “vertical development” we can speak of.

What we casually call ‘vertical development’ actually draws on (at least) three distinct academic research traditions, each examining related but genuinely different aspects of how humans grow. Recent research (from Aiden Thornton) suggests these traditions measure (and seek to develop) substantially different things, with only about 12-27% overlap between major developmental assessments. This turns out to be a feature of the field: it reveals complementary lenses rather than competing accounts of the same phenomenon.

What this means for L&D practitioners is that they need to first uncover the actual developmental needs of their clients or internally, of their teams/organisations, then understand what each tradition seeks to measure and develop, and then choose the right combination of theoretical perspectives (and psychometric tools) to build their programs in a way that effectively addresses the actual developmental needs of their target audience.

The challenge for us working in leadership development is that the academic literature, while rich, isn’t always accessible. Different researchers use different terminology. The same words sometimes mean different things across traditions, and different words are sometimes used referring to the same thing. Also. The practical implications often remain buried in methodological discussions, and there are few maps for answering the question:

“How do we actually design learning for vertical development?”

So I wrote a white paper. I aimed to provide an accessible map of the terrain while honouring its genuine complexity. Think of it as a guide for practitioners who want to understand what’s actually going on beneath the surface of the tools and frameworks they’re using.

The paper distinguishes between three research traditions, each illuminating different aspects of adult development.

Ego Development (Loevinger, Cook-Greuter, Torbert) examines how we construe ourselves, others, and the world. It tracks transformation of meaning-making, identity, and interpersonal style: the qualitative shifts in how we manage impulses, relate to others, use power, take perspective and relate to rules and norms.

Constructive-Developmental Theory (Kegan, Lahey) focuses on the progressive movement of what was “subject” (entrenched, invisible to us) becoming “object” (something we can step back from and examine). This tradition has given us powerful tools like Immunity to Change for surfacing the hidden assumptions that keep us stuck.

Hierarchical Complexity (Commons, Fischer, Dawson, Thornton) measures how structurally complex our reasoning is: how many elements we can coordinate and integrate when we think, how able we are to engage systemic thinking as we solve complex problems. This dimension is particularly relevant to strategic thinking and navigating gnarly problems with many interacting variables.

One key idea for us, practitioners, is that each tradition has its own measurement tools, and a leader who scores highly on one dimension may score quite differently on another. These traditions are measuring different (and equally valuable) aspects of developmental growth, which explains the variation and with this comes an invitation for client and consultants to choose their tools mindfully (and combine them when needed).

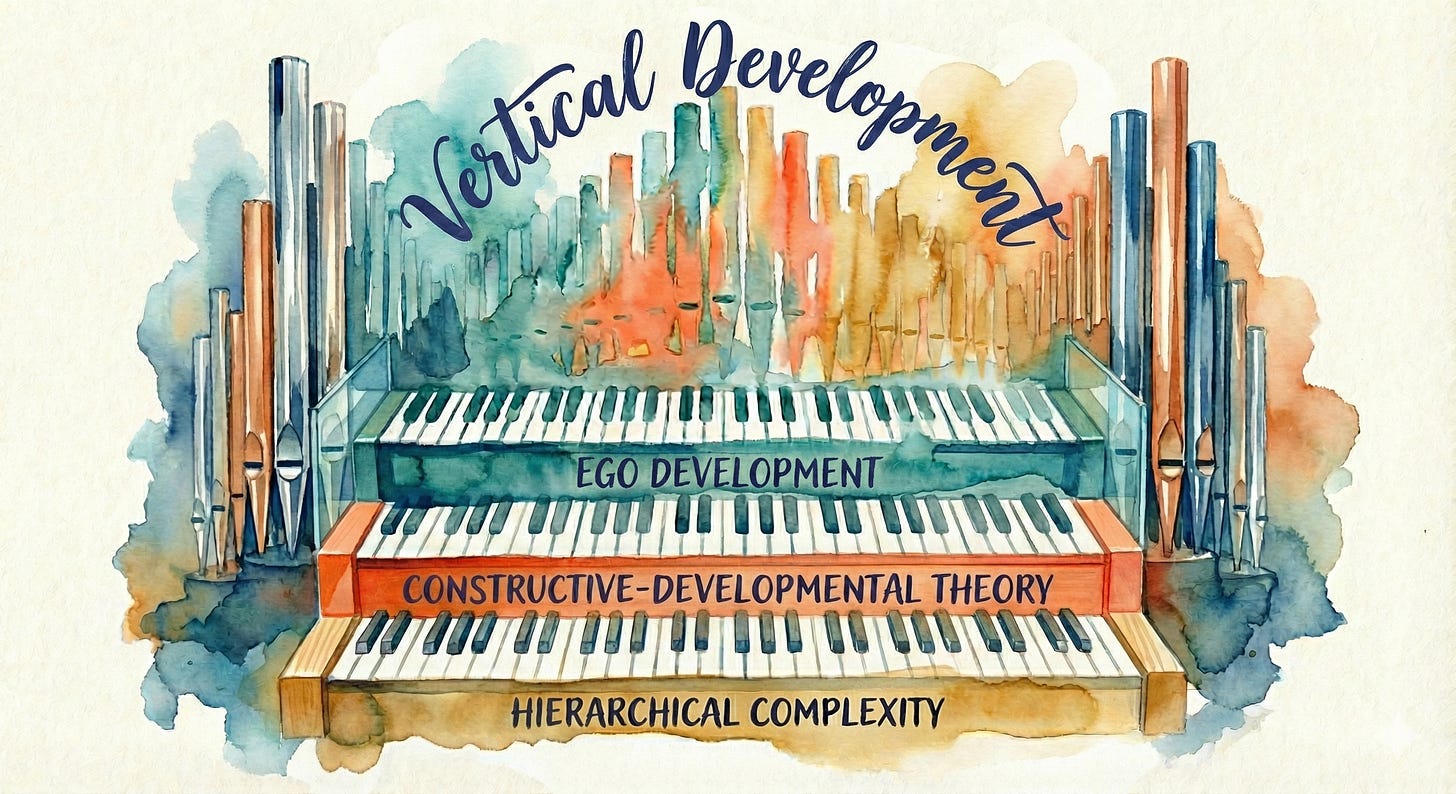

Those of you who have read this substack for a while are familiar with the piano metaphor I often use to describe vertical development (and invite a different metaphor from the ‘ladder’ image often used in the field). The ‘ladder’ suggests we leave earlier stages of development behind as we ascend, that “higher” is “better,” and that the goal is to reach the top. The piano invites a more nuanced understanding.

As we develop, we gain access to more ‘octaves’, and more notes within each octave. We don’t lose access to earlier capacities; we integrate and transcend them. We can use all our previous perspectives when we need them. A skilled pianist chooses the right notes for the right moment. Similarly, a developmentally mature leader draws on a wider repertoire, selecting what fits the situation rather than being limited to a single way of making sense.

The piano metaphor also reminds us that we can fall back. This means we can, under certain circumstances (like stress, cultural pressures, trauma) to lose our developmental capacities either temporarily or even for longer periods of time. Vertical development is, in fact, not ‘vertical’ at all - it looks more like “two steps forward - one step back” (Valerie Livesay’s work is a treasure trove on the topic if you are keen to dive deeper).

The white paper explores this metaphor in depth, including how leaders develop unevenly across what we might call “lines of development” - distinct aspects of human growth that run underneath stages, like notes making up an octave. Things like cognitive complexity, perspective-taking, self-awareness, relationship to power, time orientation, and others. You might be sophisticated in strategic thinking while remaining conventional in your relationship to power. This is normal. And it means effective developmental interventions need to target specific lines rather than simply some generic “stage.”

It also means that, in a sense, the three traditions I mention above focus, in their own way, on particular lines of development, which makes them at times seem unmoored from each other. If hierarchical complexity studies specifically the way people think, constructive-developmental approaches look closely at how they understand themselves in relation to the world, and ego-development looks at how their identity or interpersonal dynamics are shaped. A leader could think in very sophisticated ways (hierarchical complexity), but have low emotional self-awareness or self-regulation (ego-development). This means there likely is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to developmental leadership programs.

Despite different theoretical starting points, researchers across all three traditions tend to converge on what makes developmental programs work. Nick Petrie gave us two seminal white papers that laid out the foundations of how to build developmental programs. He wrote about creating heat experiences that genuinely stretch leaders’ current thinking; colliding perspectives that challenge existing meaning-making and elevated sense-making.

In my own research, I explored the role of disorienting dilemmas that create discomfort at the edge of current capacity and the way difficult emotions (so-called ‘edge emotions’ (Malkki 2010)) play a huge role in vertical development when met with curiosity instead of denial or avoidance. I also studied how facilitated reflection enables leaders to transcend old mindsets and access broader, more complex perspectives.

All existing research suggests effective developmental programs require sustained engagement over months or even years rather than intensive short-term interventions. So vertical development does not lend itself to a ‘quick fix’ approach, as is often preferred in fast-paced, hyper-busy corporate environments.

The white paper covers the three research traditions in depth, with their origins, key contributors, assessment methodologies, and business examples. It explains why different assessments measure different things, and why you might want to consider selecting psychometrics for your learning projects based on purpose rather than just familiarity. It explores the concept of developmental “lines” and why leaders develop unevenly. It presents practical methodologies from each tradition: Thornton’s pedagogical strategies, Dawson’s VCoL, Kegan’s Immunity to Change, polarity work, and the Vertical Development Institute’s own D.E.C.I.I.D.E.D.™ framework. It outlines program design principles that create conditions for genuine vertical development. It maps the landscape of developmental assessments grouped by tradition, with guidance on selection. And it sets realistic expectations about how much time and consistency vertical development actually takes.

I wrote this for practitioners who want an overview of the field with enough depth to help inform program design decisions, but without the need to wade through academic journals. This is for HR leaders, L&D professionals, coaches, and learning designers who are creating developmental programs and want to understand the science behind what they’re doing.

It is worth mentioning that I do not claim this to be a complete representation of the field, and I regard it as a work in progress that can get perfected, updated and evolve as new perspectives emerge (or feedback from other researchers points out important aspects I might have missed).

There are so many significant contributions to the study of human development that went beyond my scope (and ability to synthesise in one paper), such as work in attachment theory, wisdom research, contemplative practices, therapeutic schools of thought that impact L&D (such as IFS, or trauma work), cross-cultural work and (very importantly) Indigenous perspectives. All deserve attention in their own right. I have chosen to focus on the main academic traditions, specifically in developmental psychology and with direct implications for leadership development (program design, coaching, facilitation).

If the questions I’ve raised here resonate, if you’ve been wrestling with how to make sense of the vertical development landscape or how to integrate different approaches into your work, I hope you’ll find the paper useful. You can access it here.

If you are short on time, you might instead want to watch this short video synthesis of the paper (mind you, this does simplify things quite a bit - the paper gets into more detail and holds plenty of academic references for you to follow up).

As always, I’d love to hear your reflections. What tensions have you noticed in applying developmental frameworks in your own work? What questions do you wish had clearer answers to? Drop a comment and let’s keep learning from each other in service of helping grow those wiser, more mature leaders the world needs right now.

Dive deeper

I hope you’ve enjoyed this article. If you are curious to dive more deeply into learning about Vertical Development and how it might impact your work and life, check out our online library of webinars and certification programs accredited by the International Coaching Federation. If you choose to become a paid subscriber to this Substack, you will receive complimentary access to all our webinars and a 50% discount on our long-form online programs, including our “Vertical Development Practices for Coaches”.

If you are seeking to train as a developmental coach and get your first ICF credential, check out our ICF Level 1 Foundation Diploma in Developmental Coaching - next cohort starts in Feb 2026 (now running on Americas/Apac time zones) and we have very few places left. Check out the Program Page for details and reach out for an interview.

Spread the word…

If you want to do your bit to build a wiser, more conscious world, I hope you share this article with others who could benefit from the learning.

And, if you haven’t done it yet, subscribe!

Join your nerdy community, and let’s keep on staying curious and learning from each other.

A lovely white paper on the different lines of vertical development. But no references to Terri O’Fallon’s work in the bibliography? She’s written a number of papers that built on Suzanne’s work.

Meanwhile, too many adults will have children regardless of not being sufficiently educated about child-development science to ensure parenting in a psychologically functional/healthy manner. It's not that they necessarily are ‘bad parents’. Rather, many seem to perceive thus treat human procreative ‘rights’ as though they (potential parents) will somehow, in blind anticipation, be innately inclined to sufficiently understand and appropriately nurture their children’s naturally developing minds and needs.

As liberal democracies, we cannot prevent anyone from bearing children, not even the plainly incompetent and reckless procreators. We can, however, educate all young people for the most important job ever, even those high-school teens who plan to remain childless. If nothing else, such child-development curriculum could offer students an idea/clue as to whether they’re emotionally suited for the immense responsibility and strains of parenthood.

Given what's at stake, they at least should be equipped with such valuable science-based knowledge! ... In the book Childhood Disrupted the author writes that even “well-meaning and loving parents can unintentionally do harm to a child if they are not well informed about human development” (pg.24). … I’ve talked to parents of dysfunctional/unhappy grown children who assert they’d have reared their cerebrally developing kids much more knowledgeably about child development science.

A physically and mentally sound future should be every child’s fundamental right, especially when considering the very troubled world into which they never asked to enter; particularly one in which the parents too often stop loving each other, frequently fight and eventually divorce. Being caring, competent, loving parents — and knowledgeable about factual child-development science — should matter most when deciding to procreate. Therefore, parental failure seems to occur as soon as the solid decision is made to have a child even though the parent-in-waiting cannot be truly caring, competent, loving and knowledgeable.