Inside the Mind of a Coach. Part 1

A search for 'coaching books' returns 30k results on Amazon. Countless methodologies, competencies, standards. But what happens, really, inside the mind of a coach? Here's a glimpse into mine.

What started as an experiment in making my thinking as a coach visible, soon turned into a massive article, so I’ve chosen to split it into parts. Below is Part 1, where I share the core principles that inform my approach to coaching. In Part 2, you’ll read about the sensing and sense-making compass that guides me in every coaching conversation. Finally, in Part 3 I share some of the life practices that helped make me a better coach but, most importantly, a more conscious human being.

Those of us who train and mentor other coaches know it's not that hard to convey a list of competencies and models. Coaches in training love lists of questions, steps for the conversation, and the safety you get from having a clear map in front of you. And for good reason! The map is important. Methodologies matter and boundaries and ethical standards are crucial. But once all that groundwork is done, and people start practising, they quickly discover that the map is NOT the territory.

The same question that creates a massive breakthrough moment for a client falls flat with another. The same strategy for setting goals brings clarity to one client and is perceived as cumbersome and confining by another. Having watched and assessed hundreds of coaching sessions, while also coaching some thousands of hours over the past 16 years, I’ve come to believe that masterful coaching is somewhat of a science and very much of an art - one that I’ll never be done honing.

I’ve learnt that, beyond formal credentialling competencies and knowledge acquired over time, the embodied 'skill' of a coach is as unique as the psyche of the coach, which then intersects with the psyche of each client, and finally, both intersect with the broader context and moment the coaching is taking place in.

You coach from who you are as much as you coach from what you know and you are a different coach for every one of your clients. You are even a different coach for the same client from one session to the next. So how can you teach any of that?

As I watch coaches practice in our Developmental Coaching Diploma, I often notice small details, nuances of energy, and opportunities to ask a certain question or go down a certain path. These often go beyond the basics of “Did you set a clear goal for the session?” or “Did you ask open questions?” or “Did you refrain from giving advice?”. They are more in the realm of sensing something in my body, noticing a small grimace as the client spoke about that particular topic or noticing how they suddenly started talking in the second person (while still talking about themself) as if trying to distance themselves from something too painful to take ownership of; or perhaps picking up a word uttered one too many times, that seemed to have a particular meaning for the client. I might be noticing how the coach’s energy dropped, or a quiver in their voice or a speeding up of their speech at a certain moment in the conversation - as an unconscious reaction to something the client had said.

I always feel (but not always give in to) the impulse to share these observations with the coaches I train, to invite them to notice some of the things I notice, to wonder what else might have been possible had they pulled on a certain thread in the conversation. I always wonder how to support them to see and learn more, to grow faster. But then I know that growth happens in its own time.

The challenge is these observations seem completely eclectic. That little cue that might have unlocked something in this conversation will likely not come up in another. So even if I share it with the coach, how can they add it to their ‘tool kit’ if they might never use that ‘tool’ in the same way again?

Similarly, when I do demo sessions and someone later asks: “How did you decide to ask that particular question?” or “Why did you choose not to say anything at all at that moment?” - it’s challenging to go looking for the rationale to something that at the moment feels profoundly intuitive - a choice born out of my unique inner world in a moment of presence and attunement to the human in front of me.

I’ve long wondered if there is a hidden structure to these seemingly intuitive choices experienced coaches make. What exactly happens inside their minds as they are coaching?

What do they look/listen for in each client? How do they know a particular thread is truly important to pursue and another not so much? How do they choose their response? How do they know if one client needs more space and another needs a push? How do they tell apart their thoughts/projections from the genuine signals from the client? When they do listen to their 'intuition', what is it exactly that they are listening for and how do they do it?

As I’ve sat with these questions, I became more aware of a certain architecture of the mind, which informs my coaching approach - a sort of inner compass that guides my choices. There is a certain ‘logic’ to my intuition, which can be brought out of the unconscious space where it normally dwells. I’ve been able to track some pathways forged in my brain over time, that inform the way I make meaning of and with each client. I’ll do my best to take you down some of these paths, not to provide some recipe - as I believe our coaching is as unique as we are - but to stimulate your thinking.

Why is your approach working, when it is working? What does your version of the ‘architecture of a coach’s mind’ look like?

My coaching is informed by a few key elements, all of which work together in the moment, in every conversation with a client.

First, there are three core principles I always abide by - I find they help keep me on track. Secondly, there is a whole-body sensory system that I’ve developed over time, that allows me to attune to the client and the flow of the conversation and helps steer me in the right direction, even when I can’t see exactly where I’m going. Thirdly, there is a set of personal practices that help keep me aware, honest and continuing to grow as a coach (and, more broadly, as a human being). In this first part of this article series, I’ll share my principles. In the second part, we’ll dive into the ‘sensory-system’. And in the third part, we’ll explore some practices.

The principles.

As a coach, I am in service to the client. Always.

Not to my ego. Not to my need to help/fix/save the client. Not to my intellectual interests. Not to my need to be liked or needed. This means that every decision I make as a coach - within every session and in the coaching process as a whole - is informed by this core question:

Is this for myself or the client? If it’s for myself, then I don’t say/do it. If it’s for the client, even if it’s uncomfortable, I go ahead.

In practice, this means that I am careful to take time to help the client understand what they want (not what they don’t want) and I follow that thread as my guiding light throughout every conversation. I coach the client on what they need, not what I think they need.

It also means I diligently work to make myself redundant. My true success as a coach is when my clients don’t need me anymore. This helps me do everything I can to empower my clients, to get them to ‘do the work’, and to put the onus on them to find their own answers, always.

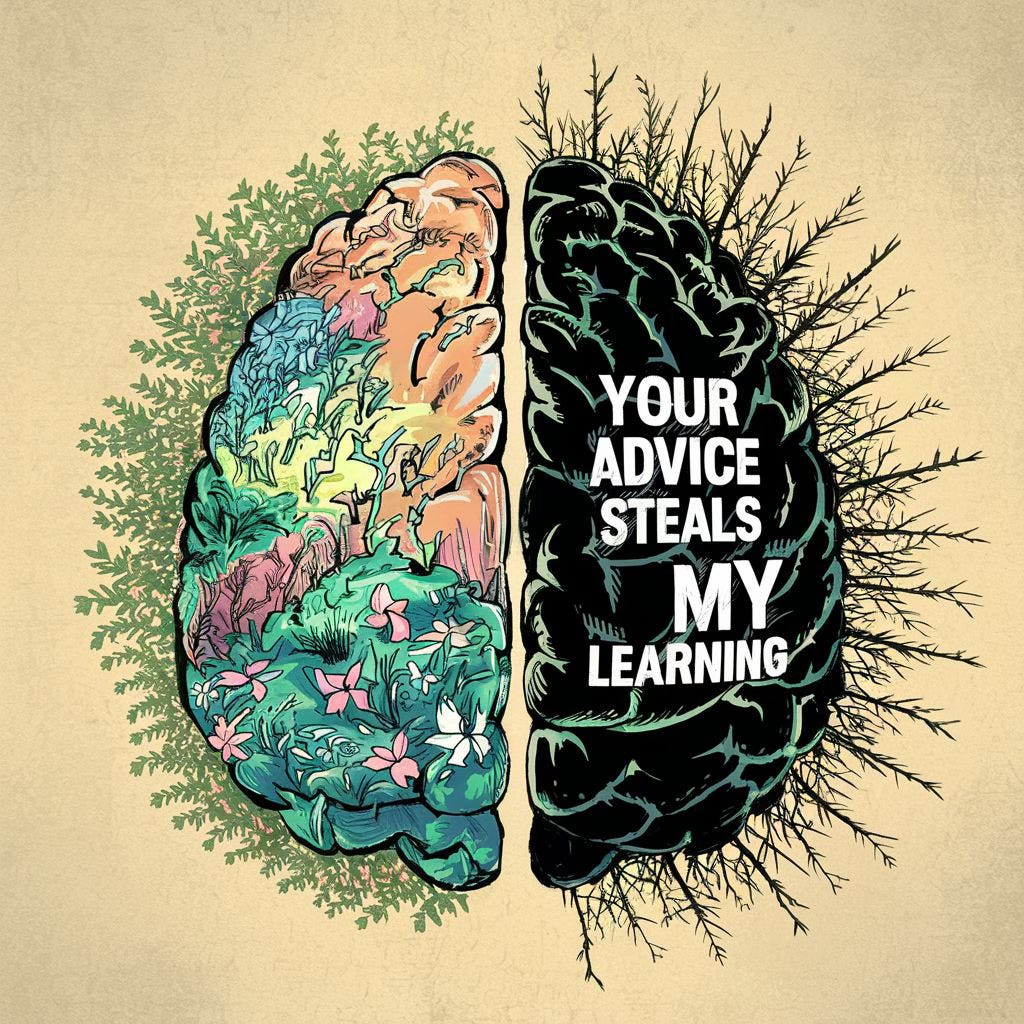

This has been my best antidote against the trap of sharing unneeded opinions or advice - one that so many coaches struggle with as they start in this profession. By giving advice, am I still serving the client? Am I empowering them to not need me anymore? Most of the time, the answer is NO. In fact, by giving advice, I’m likely to steal their learning.

This same principle informs the questions I choose to ask in a session. I often see coaches in training asking a lot of questions about the client’s context, rather than the client themself. That often comes from the coach’s need to understand (and the underlying assumption is that if we understand more, we can help more). When clients talk about their context, they tell you things they already know. They’re not reflecting, or learning anything new. They are just conveying their stories and they feel good doing that too, because it’s great to ‘download’ in front of an empathic listener. Meanwhile, the coaching conversation isn’t moving forward.

Here are some questions I ask myself to make sure my inquiry stays truly helpful to the client:

Is this question in service of the client and their intention for this session? Is this question taking them closer to what they want to gain by talking to me today? Is this question about the client (rather than their context/other people)? Is this question bringing the client closer to a resolution or getting us on tangents? Is this question empowering the client - inviting them to take responsibility for their actions or giving them an excuse to talk about other people? Is this question inviting the client to reflect more deeply or just prompting them to tell stories they’ve told (themselves) many times before?

This same principle of always staying in service to the client also helps me find the courage to challenge my clients, to create developmental discomfort because I truly believe that will benefit them. This brings me to the second principle.

Humans grow through a careful balance of challenge and support.

My research in adult (vertical) development has shown that the right balance between challenge (being taken out of the comfort zone) and support (being in a trusting, psychologically safe space) is crucial to human growth. As I studied a group of executives going through a long-form leadership program, I consistently found that the leaders who had measurably grown (vertically) post-program had experienced this ‘magical’ balance within their peer-coaching groups and also in the program as a whole.

This finding has had a huge impact on my coaching. It made me much braver in asking difficult questions that invite my clients to confront actions or parts of themselves that are not easy to see. How do you contribute to this conflict? - is but one small example of a question I might not have asked a client so readily a few years ago. I am less worried about my client’s potential defensiveness than I used to be.

This same principle has also confirmed my prior values around care, empathy and compassion for my clients. Care had never been an issue for me. But the courage to challenge did not come easy.

I am noticing in the coaches I train that many have a preference for one or the other. Some are warm, caring and so gentle that they never disturb a client’s mental status quo for fear of being intrusive or causing discomfort (or sometimes for fear of no longer being liked by the client). Others go for the opposite pole. They ask incisive questions way before having enough rapport with the client and without investing time to build trust and a space of ‘unconditional positive regard’ where the client can welcome the challenge and feel open to being made uncomfortable.

I encourage coaches to notice what is their preference and to explore what might help them tap into the opposite pole.

I also use this principle to guide me during a coaching conversation - I might spend time listening and allowing the client to ‘download’ as I feel they need to take things off their chest. But then I might notice they need a little jolt, a bolder invitation to reflect, to notice self-defeating patterns or tap into something hard they might have been avoiding. I might bring in some challenge to ‘spice up’ a coaching session that feels too ‘tame’ or neutral.

I am constantly, as a coach, turning the client’s attention towards themselves, while making it safe for them to face whatever it is they will find within. And I trust they will get to where they need to. Which brings me to my third (and last) principle.

People can and do change. In their own time. A coach’s job is to be ‘undisappointable’.

My third core principle allows me to be patient. It’s helped me let go of my own need for results in coaching and trust that my clients will make their shifts, in their own time. It was born out of lived moments of despair when a leader I was working with seemed beyond change and then, it turned out, they weren’t.

The most memorable example was a long time ago when I worked with a group of young leaders in a small financial services company run by a brilliant enthusiastic and visionary entrepreneur. He had gathered around him, over 10 years of building the business, a small and passionate team and together they had grown the company beyond all of their wildest dreams. Now time had come for the CEO to consider succession and he wanted me to coach his highest potential employee.

This gifted young man, in his late twenties, offered one of the most incredible examples of asynchronous development (some aspects more developed than others) that I’ve seen. Cognitively, he was brilliant. Sharp, witty, connecting the dots way ahead of anyone else. He cared deeply about the company. The quality of his work was outstanding. Clients loved him. His teammates not so much.

This was a man who had set up a mobile wall within a friendly and informal open office so his peers would know not to disturb him. Part of his role was to check the work of junior consultants before it got sent to the client. He had a red pen to mark all the mistakes he found in every report that crossed his desk. He openly told me that the only reason he was meeting with me was because he deeply respected his boss and he had told him that his ‘people skills’ needed improvement. He said:

“But I think others’ quality of work needs improvement! If they made fewer mistakes I would not have to give them so much feedback. And I can’t understand why someone would get upset from receiving feedback!? I just want them to learn - wha’t wrong with that?”

We met for a couple of sessions, in which every single attempt at turning a mirror towards him failed. We lost contact for the next couple of years. Then, all of a sudden, he reached out to apply to join my coaching school. He wanted to train as a coach.

I read his email and my first thought was that it was a joke. Then, when we met, I could not believe this was the same person from two years previously. He looked the same as the last time I’d seen him. His discourse was as direct as before. But his energy was completely different. He spoke more calmly. He asked more questions. He told me how our short encounter two years previously had opened up something in him, and then a series of events in his life had led to a reckoning of sorts.

He had finally realised his impact on others. He had managed to see the dark side of his drive for excellence - the perfectionism that had led him to relentlessly criticise and push the team, the demotivation he had sparked, the impact this had had on the team morale and ultimately the threat it had caused to the business. He had realised how deeply he cared about his colleagues and how much he wanted to help them grow, but how toxic his approach had been. He went on the coaching program and was one of the most considerate, discerning and empathic coaches I have ever trained!

If you had asked me if this man had it in him to become a professional coach, I would have said ‘Not in a million years’! But that was years ago. Now I am (hopefully) a bit wiser. You never know what a person might become! Now I step into each client relationship with unrelenting hope for my client’s capacity to grow. How fast? How far? I’ll never know. But this trust helps me stay patient. Meet the client where they’re at and challenge them one step at a time.

I don’t believe that a coach’s measure of success lies in how fast clients change. I think it lies in how deeply you can accept your clients for who they are and how much you can trust their potential to become more, however messy the road might be to them getting there. It lies in your patience to step alongside them on that winding path. Sometimes it lies in your generosity to let them go if they’re not ready and trust they will come back if they ever are. As a client of mine said:

The biggest gift you’ve given me was that you have been ‘undisappointable’.

It is to this day the most beautiful feedback I’ve ever received. I strive to pay it forward. In working with other coaches and supporting them through the frustrations of trying, failing, learning and growing, I ask myself this question:

How might I continue to stay ‘undisappointable’?

This is the end of Part 1 of the series “Inside the Mind of a Coach”. Next week I’ll invite you to Part 2, exploring the cognitive/sensory/somatic landscape of my mind during a coaching session. I’ll strive to explain how I make sense of the client’s words and narrative thread, how I choose to ask certain questions (and not others) and how I practice staying aware (and utilising) the process (HOW) of the session as well as the content (WHAT).

Dive deeper

I hope you’ve enjoyed this article. If you are curious to dive more deeply into learning about Vertical Development and how it might impact your work and life, check out our online library of webinars and courses accredited by the International Coaching Federation.

If you are seeking to train as a developmental coach and get your first ICF credential, admissions are now open for the next group of our Foundation Diploma in Developmental Coaching starting in July. Check out the Program Library for details and reach out for an interview.

Spread the word…

If you want to bring your bit to building a wiser, more conscious world, I hope you share this article with others who could benefit from the learning.

and, if you haven’t done it yet, Subscribe!

Join your nerdy community and let’s keep on staying curious and learning from each other.

This article resounded on several levels. 𝐼𝑠 𝑡ℎ𝑖𝑠 𝑞𝑢𝑒𝑠𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑖𝑛 𝑠𝑒𝑟𝑣𝑖𝑐𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑐𝑙𝑖𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑖𝑟 𝑖𝑛𝑡𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝑡ℎ𝑖𝑠 𝑠𝑒𝑠𝑠𝑖𝑜𝑛? In asking this questions the coach would have to acknowledge their ego (and make it not part of the answer) and to have the authenticity not be trigger. The way I come from is sensing the question the clients system wants to be asked.

Thank you for this beautiful tesimonial of your coaching approach, and for popping the hood with these profound principles! I wonder if you might elaborate on your assertion that "your advice steals my learning". I've noticed that there's a polarity there between "asking" and "telling"... If I am always asking clients to reflect and tell me what they think, the energy slows down, and in a sense I find that there's a "pointing out" that I could be doing that would immediately open up their perception to a new possibility. In other words, at times, it's in my "not telling them" that is robbing them of the opportunity to grow. Sometimes the most profound insight and transformation comes when I simply offer a new story or model or principles that gives them something to chew on and reflect on it within the context of their own experience. How does this land for you?